History of AI

The origins of AI can be traced back to the pioneering work of Alan Turing during and after World War II. Turing’s codebreaking efforts at Bletchley Park, where he developed techniques to decrypt the German Enigma machine, laid the groundwork for computational theory. In 1950, Turing published his seminal paper "Computing Machinery and Intelligence," proposing the question “Can machines think?” and introducing the Turing Test as a criterion for machine intelligence. His ideas profoundly influenced early AI research, inspiring scientists to explore the possibility of creating machines that could simulate human cognition.

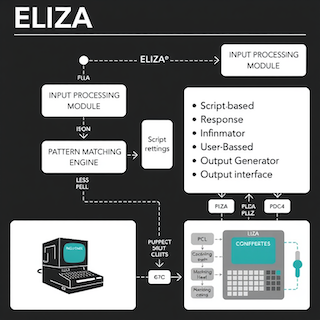

The term "Artificial Intelligence" was coined at the Dartmouth Conference in 1956, a seminal workshop attended by luminaries such as John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Allen Newell, and Herbert A. Simon. This event marked the official birth of AI as a research field. Early AI programs like the Logic Theorist, created by Newell and Simon, demonstrated that machines could perform symbolic reasoning and prove mathematical theorems. Another milestone was ELIZA, developed in the 1960s by Joseph Weizenbaum, which simulated conversation by mimicking a psychotherapist. These programs showcased the potential of AI to replicate aspects of human thought and interaction.

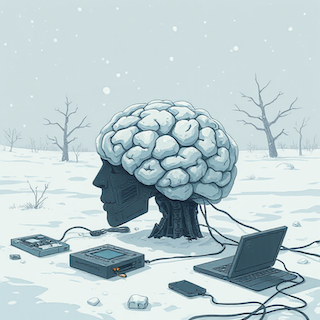

Despite early enthusiasm, AI research faced significant setbacks during the 1970s and 1980s, periods often referred to as "AI winters." These were caused by a combination of limited computational power, insufficient data, and the immaturity of algorithms. Many AI systems struggled with scalability and robustness, leading to unmet expectations. Consequently, funding and interest waned, slowing progress and causing a more cautious approach to AI development in subsequent years.

The 1980s saw a resurgence of AI research through expert systems, specialized software designed to emulate decision-making in specific domains. Notable examples include MYCIN, which assisted in medical diagnosis, and XCON, used for configuring computer systems. These systems leveraged rule-based logic to provide practical benefits, such as improved efficiency and consistency in expert tasks. However, their reliance on handcrafted knowledge bases limited adaptability and scalability, highlighting the need for more flexible AI approaches.

A landmark event occurred in 1997 when IBM's Deep Blue, a chess-playing computer, defeated the reigning world champion Garry Kasparov in a highly publicized match. Deep Blue utilized specialized hardware and advanced search algorithms to evaluate millions of positions per second, demonstrating the power of computational brute force combined with strategic heuristics. This victory symbolized a new era in AI, showcasing the potential for machines to outperform humans in complex, strategic tasks.

The 21st century ushered in transformative advances driven by the availability of massive datasets ("Big Data") and enhanced computational power, particularly through GPUs optimized for parallel processing. The breakthrough moment came with the success of deep learning techniques, exemplified by the ImageNet competition in 2012, where neural networks dramatically improved image recognition accuracy. Today, AI technologies power applications such as voice assistants, autonomous vehicles, medical image analysis, and natural language processing, fundamentally changing how we interact with technology.

The history of AI reflects cycles of optimism, setbacks, and breakthroughs. As AI continues to evolve rapidly, it is crucial to develop ethical frameworks addressing privacy, fairness, accountability, and societal impact. Responsible stewardship will ensure that AI technologies contribute positively to humanity, balancing innovation with thoughtful consideration of the challenges ahead.

The Beginnings

The Birth of AI

Setbacks and AI Winters

New Momentum from Expert Systems

Breakthrough in the 1990s

Modern AI – Big Data and Deep Learning

Conclusion and Outlook